Artwork by Denise Barry

Mixed media, 2015

Oh if only the turquoise ocean can speak

The wizard wind carries lonesome melodies

echoing memories of the past hundred years

of schooners, luggers, pearl shells,

and waves of settlers called Manilamen

washed ashore in the Torres Strait and Broome,

their descendants and offsprings

of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait islanders

with new arrivals on their trail

sing songs that graft new tunes into old,

the ancient songlines with tracks on rocks and soils

of mixed identities fused.

The red sandy soil stirs up old memories

that honour forebears who dived

in the depths of the continent’s soul

with black women who took the lead,

embracing mixed traditions,

their gaze never quite turned away

from their roots, the distant islands of their dreamtime

from where their ships had sailed away.

The discovery of rich pearling fields in Northern Australia helped

the development of the Northwest and Torres Strait. From 1800 to

1850, trade routes in Australia brought hundreds of sailing ships

from Brisbane and Sydney through the Torres Strait and onto ports in

India and other parts of Asia.

From the 1860s-1870s,

pastoralists, who established stations around Roebourne in Pilbara,

started pearl shelling operations in Cossack during their low season

using Aboriginal people’s labour.

The Pearlshell Fishing

Regulation of 1871 and the Pearlshell Fishery Regulation Act of 1873

controlled the involvement of Aboriginal people to protect them from

gross abuse. The prohibition of Aboriginal women as divers created

an acute shortage of labour that was filled by the importation of

Asian workers.

These were mainly impoverished ethnic

Chinese, Malays, Filipinos, men from India, Batavia (the Dutch East

Indies), and other islands to the north of Australia who were

indentured in the farming, pastoral and pearling industries.

"Everybody worked in it from the Europeans

that owed it to the Japanese, the Filipinos, the

Malaysians, Indians—all these nationalities of

people who came out here that made Broome."

-Elsta Foy

Manilamen descendant

As the pearling industry was being developed in Australia, in the

Philippines, political events challenged the Spanish colonial

authority. What began as a reform movement led to the Philippine

revolution in 1896, compelling some ‘natives’, mostly entrepreneurs

and sojourners, to move abroad, including Australia.

By 1884, a newly arrived Catholic priest found 40 Filipinos living

in Thursday Island in Australia. “Four hundred Catholics from

Manila” were scattered among various islands, with the

best-documented and longest-lasting community being in Horn Island,

south of Thursday Island.

Filipinos were referred to as ‘Manilamen’, ‘Manillamen,’ or simply

‘Manillas,’ despite not necessarily originating from the capital,

Manila. In the late 1880s Northern Australia, Manilamen at times

found themselves categorized as ‘Malay’, a generic term referring to

Southeast Asians such as those from Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore,

Thailand, and East Timor.

“I can remember all the Filipino people; all the old men

worked in the bakery, my grandfather’s bakery. Some of them

lived across the bay in Fishermen’s Bend.”

- Evelyn Masuda

Manilamen descendant

Manilamen

were not just seafarers but labor

migrants who were part of a global working class.

They worked onboard vessels in the maritime world

that linked the Philippines to Asia, Africa, the Americas,

Australia, and Oceania. Some stayed only temporarily

for work while others found themselves settling

in a new territory.

Manila divers in Sunday attire, circa late 1890s or early 1900s

Photo courtesy of State Library of Western Australia (slaw_b1926943_1).

An unknown number of political exiles who were active in the

Philippine revolutionary movement also came to Australia, including

pearl divers Candido Iban and Francisco del Castillo, who arrived in

the late 1880s or early 1890s. Upon their return to the Philippines,

del Castillo was appointed Chief of Katipunan Chapter in Capiz, with

Iban as his assistant. Both died in a military encounter in Aklan,

Philippines.

The political sentiments of Heriberto Zarcal, one of the earliest

Manilamen who landed on Thursday Island in May 1892, can be gleaned

from his naming of his two-storey building, Noli Me Tangere (Touch

Me Not), the title of the novel by Philippine national hero, Dr.

Jose Rizal. One of his luggers, Kavite, probably commemorates the

1872 uprising in Cavite, Philippines after the Spanish authorities

executed three local priests—Fathers Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos, and

Jacinto Zamora.

Two other Manilamen, Valeriano Dalida

and Albino Rabaria, donated their savings to purchase a printing

press in Hong Kong, eventually resulting in the publication of the

propaganda newsletter and primer, Cartilla and Kalayaan with the

Diario de Manila.

“My father talked about Luzon [in the Philippines] a lot...

He wanted to get away from there. I don’t know what was

happening there about the people’s revolution against Spain

that motivated some Filipino men to leave the country.”

– Mary Manolis

Manilamen descendant

Noli Me Tangere, Heriberto Zarcal's building on Thursday

Island

Photo courtesy of Illeto & Sullivan, 1993. Discovering Australasia:

Essays on

Philippine-Australian Interactions.

Kavite, one of Heriberto Zarcal’s luggers, small vessels about

9-10 metres long used in the pearl-shell industry

Photo by Tom McDonough, Broome, circa 1930s. Courtesy of Lynn

McDonough.

In the last years of the 19th century, Thursday Island was

the centre of pearl shelling and other maritime industries,

and Filipinos were working mainly as divers and trepangers.

Innumerable Manilamen arrived in Western Australia from the late

1860s, and were recruited to work as pearl divers in Cossack and

later in Broome in the Northwest and in the Torres Strait.

In Broome, they also worked as crew, shell openers, sorters, and

captains, also becoming fishermen, woodcutters, kitchen hands,

proprietors or boatmen. By 1901, 279 Filipinos were working in the

pearling industry in Broome, along with Koepangers and other Malays.

The growth in the pearling industry also hastened the development of

Thursday Island. By 1874, Filipinos and Pacific Islanders were

already working in the industry in Torres Strait with indentured

labor replacing individual agreements. In August 1899, the steamship

Changsa arrived in Thursday Island with 72 Filipinos onboard under

private agreement to work in the pearling trade.

In the last years of the 19th century, Thursday Island was the

centre of pearl shelling and other maritime industries, and

Filipinos were working mainly as divers and trepangers.

“Telesforo went back to the Philippines. He took my mother and my

younger

brothers and sisters… we don’t have the Aborigine blood because my

mother

you see, [was] Japanese, not that I… I wouldn’t object to that…”

- Magdalene Ybasco

Manilamen descendant

Most Manilamen in Northwest Australia and Torres Strait Islands were

Catholics who married local women. In Broome and Thursday Island,

they made strong and lasting links with Catholic missionaries. The

minority who were Muslims were often referred to as Malays.

To Filipino descendants, their forebears helped build the social and

economic foundations of Broome, Horn Island, Hammond Island, and

Thursday Island. Australia’s policies toward migrants, along with

competition with Europeans in the pearling industry, made life

difficult for the Manilamen and their families. Some, however,

managed to rise up the ranks and established their own businesses.

Stories of the rich social and family life of Filipinos—their music,

song and laughter—despite challenges in their new home, are memories

treasured by the descendants.

“[Manilamen] created a sort of sub-Creole culture because of their

intermarriage

into the Aboriginal culture of this town... the sound of music that

no one else has.

You can attribute it right back to those Manilamen because they

introduced their

banjo and mandolin and harmonica in our community.”

- mitch torres

Manilamen descendant

Settlers in Australia

Intermarriage and Naturalization

Settlers in Australia

Intermarriage and Naturalization

Naturalization

“We could say that we are descendants of each side [Filipino and

Aboriginal], you know… It was just like a

stigma, you know for men to be involved with an Aboriginal wife, so

that’s why they didn’t marry…”

– Ellen Puertollano

Manilamen descendant

White of half-caste

and movement, through the ‘Common Fence,’ originally

used to keep the cattle out, in Broome. The wire fence

was conveniently used to regulate the entry into

the town of Aboriginal people with no work permits.

“We used to have quite a few strikes because the

picture show was segregated. If a coloured man or

a black man sat where they shouldn’t have

because it was reserved for whites only, they’d get

kicked out or thrown out…”

- Sally Bin Demin

Manilamen descendant

“I experienced how Aboriginal people were

removed from the town site after 5PM daily. It

was known as the Common Fence. Any

Aboriginals who were inside the fence line, would

be penalised and go to jail… I was only about

four to five years old.”

- Anthony Ozies

Manilamen descendant

“There was a place called Common Gate where

Aboriginals and part—Aboriginal people could

have activities there; they had their dances which

were very good. We lit fires everywhere… It was

good because we were all happy.”

-Mary Manolis

Manilamen descendant

Intermarriage and Naturalization

The Manilamen and their Descendants

Intermarriage and Naturalization

The Manilamen and their Descendants

Puertollano Catalino

Torres Severo

Corpus Antonio

Ozie(a)s Nicholas

Sabatino Amasio

Santiago

& Cornelius

Tolentino Telesforo

Ybasco

& Basilio

Marquez Agostin

Cadawas Nicholas

Albaniel Marcello

Fabila &

Gregorio

Torricheba Magno

Lloren

Artwork by Denise Barry

Mixed media, 2015

Racial Segregation

Keeping the Filipino Connection

Racial Segregation

Keeping the Filipino Connection

Thomas Puertollano arrived in Australia on the S.S. Australind schooner from Singapore on 12 October 1889, and worked as a pearl diver. He was originally from Sta. Cruz, Marinduque, Philippines, born to Victorino Puertollano and Barbara Pampilo. His wife, Agnes Guilwill Bryan, was daughter of aboriginal woman Kanondion, and white man Bryan William Martin Bryan. Thomas and Agnes had six children who were raised in the communities of Beagle Bay, Disaster Bay and Lombadina.

Working with Father Nicholas Emo, a Trappist priest, Thomas built one of the first churches in Lombadina. He also gave his own house to the St. John of God Sisters. In Broome, he also built one of the first bakeries. Even though he applied for citizenship to Australia, he passed away not having gained naturalization in the country.

The narrators, Kevin Puertollano, is Thomas’ great grandson, while Evelyn and Ellen are his grand daughters. When Kevin was about six years old, Marcelo Querdo, an old Filipino man lived with them, whom they called lulu. Marcelo was born in the Philippines in 1885 and arrived in 1898 to Australia.

“I know I have been asked many times if I am Filipino or an

Aboriginal. And I say, well, I can’t help myself. The Filipinos

came here and they had an influence in the place, and in me.

I can only be me…”

– Kevin Puertollano

Thomas Puertollano

Evelyn Masuda & Ellen...

Thomas Puertollano

Evelyn Masuda & Ellen...

“[The Filipino people]...have their garden there in

Fishermen’s Bend or Kunin… (’kanin’ is Tagalog for

rice). I don’t know whether that was an Aboriginal

name or a Filipino name… I can’t remember mixing

with any other people, only just the Filipino

people, and not even with the white people.”

– Evelyn Masuda

Kevin Puertollano

Kevin Puertollano

Catalino Torres was born in 1875 in Manila, Philippines.

He arrived in Australia on June 1884, marrying Matilda Ida Tiolbadonga in Beagle Bay four years later in 1898. He had had four children with Matilda, who was of Jabirr Jabirr and Bard ancestry.

Sally Bin Demin, one of the narrators, is the granddaughter of Catalino Torres. Her mother, Mary Barbara, along with her sister Bella Lynott, were taken to Beagle Bay in 1909 as children because of the government policy which removed half-caste children from their Aboriginal mothers. They were placed in missions of governmental institutions.

mitch torres one of the narrators, is the great granddaughter of Catalino Torres. Her father is Casimier, one of Joseph’s children. Sally Bin Demin, another narrator, is granddaughter of Catalino from his daughter, Mary Barbara.

On the Aboriginal Filipino community: “The strongest

thing that came from that culture was the

gathering of family, being strong in the faith of the community,

Catholicism, the sharing. The music talent

was passed down, the love of dancing, the love of

gathering, and eating food together.”

– mitch torres

Catalino Torres

Sally Bin Denim...

Catalino Torres

Sally Bin Denim...

“We loved being who we were. This was our town

and if you didn’t like it, you just kept moving. We

(Asian Aboriginals) were the majority, three quarters

of the town… We came to Broome in 1945 [and]

stayed in the orphanage for a while... They (parents

of children) had to get jobs straight away or the kids

would be taken off them and sent away.”

- Sally Bin Demin

mitch torres

mitch torres

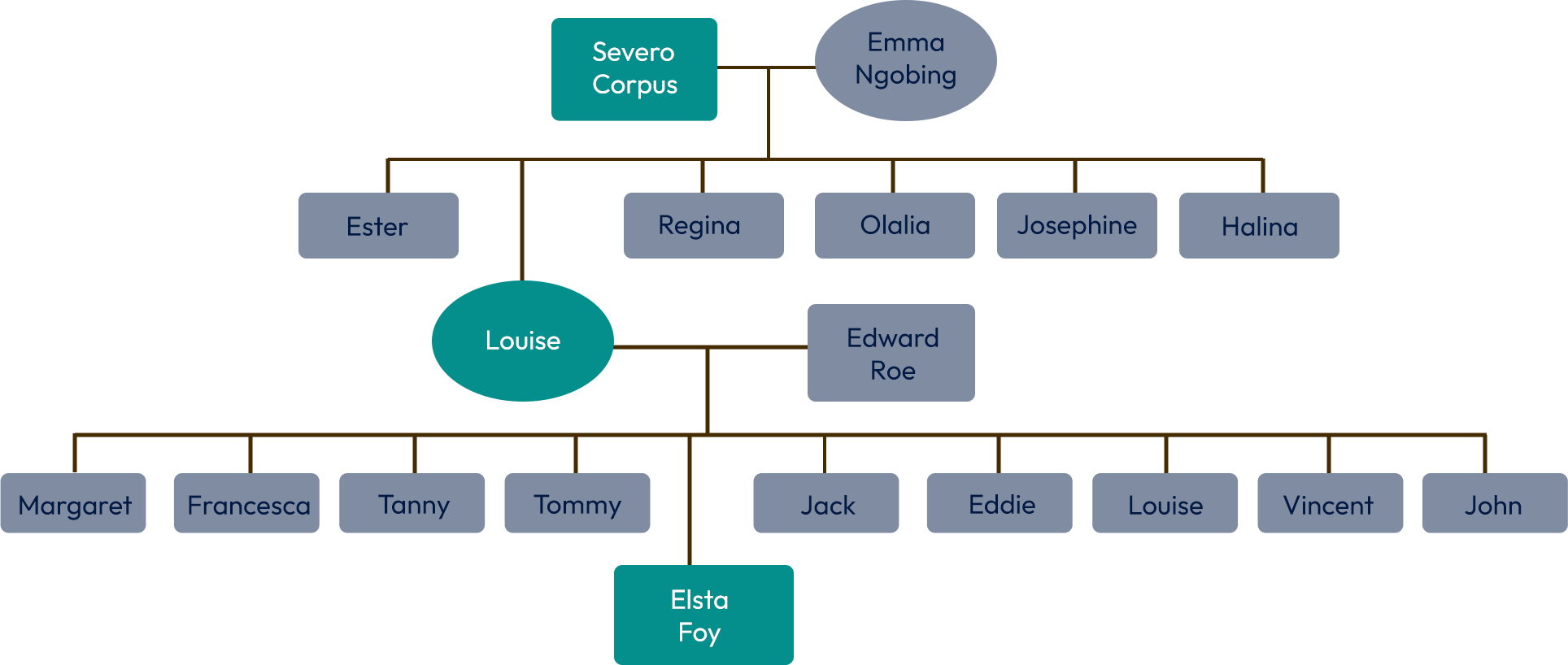

Severo Corpus worked as a pearl diver in Broome. His date of arrival is unknown. He married a Yawuru woman, Maria Emma Ngobing (or Pelean) on 4 May 1898. They had six daughters—Ester, Louise, Regina, Olalia, Josephine and Halina. Two died in childhood.

Aside from where he lived with his family, he had another house at Thangoo where he built a little jetty at a creek, which later became known as Severo’s Creek. Severo first worked as a diver and boat repairer, and later started his own business by providing the pearling luggers with fresh water, wood, and other supplies.

Elsta Foy, described her grandfather as very strict and religious. Elsta’s father, Edward Roe was known for speaking up against discrimination of other Asians. He managed two butcher shops and owned a café in Chinatown.

“...our pearling town... Everybody worked in it from

the Europeans, that owed it to the Japanese,

Filipinos, the Malaysians, Indians… that made this

town... all these nationalities of people who came

out here that made Broome.”

- Elsta Foy

Severo Corpus

Severo Corpus

Antonio Cubillo Ozie(a)s came to Australia in November 1887 and worked as a pearl diver in Broome. He was

born in July 1867, and hailed from Mindanao, Philippines. He later worked as a yardsman at the Continental

Hotel in Broome and at the Broome Shire. He married Cecelia Nganagon, a Djugun aboriginal woman from

Broome, and together had a son, Phillip.

Phillip married Dominica Fitzgerald, a mixed-race woman from Halls Creek, whose mother was an aboriginal

Kija. They had seven children, Anthony, Francis, Cecelia and Philipena. After Phillip died, Dominica re-married

and had three children, Annie, Daisy and Carim.

The narrators, Anthony Fitzgerald Ozies was Antonio’s grandson, while

Yisah is Anthony’s granddaughter.

“Most of the people here eat rice… ’Cause they, the Filipinos brought it here in

the early days, rice!.. I used to rebuild the engines up. In the old days, they

never had any engines then, they used a hand pump only. For the divers, they

sailed with no engine, just by the sails.”

- Anthony Ozies

Anthony Ozies

Nicholas Sabatino...

Anthony Ozies

Nicholas Sabatino...

Nicholas Sabatino was born in 1871 in Iloilo, Philippines. He went to Torres Strait and married Johanna Lohado. Johanna’s Filipino father, Antonio Lohado, was from Antique, Philippines, and her mother, Nancy Saki, was of Kaurareg ancestry and born in Burke Island. The Kaurareg are the traditional owners of the Inner Islands in the Torres Strait. Nicholas and Johanna had eight children, Francis, Lucio, Stanislaus, Tino, Monica, Lucy, Patranella, and Mary.

Mario Sabatino, the narrator, is a great grandson of Nicholas. His father, Lucio, was the second son of Stanislaus and Camilla Durante.

His Filipino lineage can be traced to three Manilamen—Sabatino, Lohado and Durante. Sabatino was from Iloilo, Lohado from Antique, and Durante was from Samar, Philippines.

“During my teenage years, I was constantly reminded of the great seafaring traits possessed

by both Filipinos and Islanders… I was soon drawn into working on the sea, and it turned out

to be like second nature for me.”

- Mario Sabatino

Anthony Ozies

Amasio Santiago and Cornelius Tolentino...

Anthony Ozies

Amasio Santiago and Cornelius Tolentino...

Cornelius Tolentino was born in 1873 in the Philippines and arrived in Australia around 1902. He had a family back in the Philippines—her wife Christina and sons, Pascal and Paul, and Juanita. After his wife died, he married Teresa Santiago from Idarr country.

Teresa’s father was Manilaman Amasio Santiago, who was from Capiz, Philippines and arrived in Australia in 1887. He died in Broome on 10 February 1912. Her mother was a full-blood Aboriginal woman.

Cornelius and Teresa had five children, including Mary Manolis, the narrator. Her family lived at Front Beach, Broome. Mary also recounted other Manilamen families in their community—Thomas Puertollano, Thomas Ybasco, Severo Corpus, Sariego, Trankellino, Tolentino, Ozies, Rodriguez, Bargas and Torres.

“My father always used to say, “you’ve got to call the Chinese old people, ‘lulu’ [‘lolo’

in Tagalog refers to grandfather]…”

- Mary Manolis

Nicholas Sabatino

Telesforo Ybasco and Basilio Marquez...

Nicholas Sabatino

Telesforo Ybasco and Basilio Marquez...

Telesforo Ybasco was from Camarines Norte, Philippines and came to Broome after 1901, working as a pearl diver until his retirement. Telesforo was also known as Broome’s first barber.

He married Theresa Marquez, who was of Filipino-Japanese heritage, in Beagle Bay in November 1917. Theresa was an orphan among the aboriginal group brought up in the Beagle Bay Mission.

Her mother was Omito Serotama, and her father was Basilio Marquez. Basilio is a Manilaman who was born in April 1861 and came to Australia in 1879, where he later worked as a diver in Broome. Telesforo and Theresa had twelve children. They later went back to the Philippines with their younger children, Annie, Theresa, Betty, Peter, James, and Rosie.

Magdalene, the narrator, is their sixth child. She recounted that her siblings got married and settled in the Philippines. Magdalene left

Broome when she was 15 years old and married a former prisoner of war, Camille Edward Van Prehn. They lived in Holland for 30 years

before returning to Australia.

“I’m not really Aborigine… I feel like one… I really don’t feel any

higher than them. I love them. They really love me, my Aborigine friends.

They’re half-and-half like us, half-Filipino, half-Aborigine. But really,

the closeness in Broome, you can never achieve it in Sydney.”

- Magdalene Ybasco

Amasio Santiago and Cornelius Tolentino

Agostin Cadawas...

Amasio Santiago and Cornelius Tolentino

Agostin Cadawas...

Agostin (Augustin) Cadawas was born in 1865 in Santa Yloco (Ilocos) in Luzon, Philippines. He came to Torres Strait possibly in the late 1800s or early 1900s, arriving in Yam Island in a long fishing boat with a house. He met and married Lavinia Ware and had two daughters, Anacleta and Josephine.

A firm Catholic, Agostin sent his daughters to a Catholic orphanage in Thursday Island when they grew up. Agostin was called ‘naked diver’ because he did not use a breathing apparatus and special suits. He fished for sea cucumbers, a sought-after delicacy in Asia, which used to teem in the Torres Strait.

His Certificate of Registration of Alien in 1917 described him as 4 feet and 11 inches tall, with brown eyes, grey hair, and a tattoo on the right arm. Agostin died at a very old age and was buried in Yam Island.

Josephine David-Petero, is the great granddaughter of Agostin. Her grandmother Anacleta married Younga David, with whom she had three children. Their eldest, Jack Louie, married Ladda George and they had three children, including Josephine.

“Miss, how come you’re dancing? You’re not a Filipino! I’m a Filipino

descendant. My great grandfather was a Filipino.”

– Josephine David-Petero

Agostin Cadawas

Nicholas Albaniel...

Agostin Cadawas

Nicholas Albaniel...

Nicholas Albaniel was born in 1879 in the Visayan Islands, Philippines to Marcos Albaniel and Ygnacia dela Rosa. He was one of the twelve Filipinos who went to Papua New Guinea in the 1880s as part of the missionaries.

Nicholas married Rosy Bombay, daughter of John ‘Juma’ Bombay with a part Torres Strait Islander and part Australian Aboriginal woman from New Norcia missions near Darwin. Nicholas and Rosy had six children—Emmanuel, Joseph, Nicholas, Mary Mecedes, Catherine (Katie) and Ligouri Albaniel.

Katie married Pedro Torrisheba, son of Manilaman Gregorio Torricheba, who was born in 1869 in the Visayan Islands, Philippines. Ligouri, on the other hand, was married to Salvatore Kala Fabila, son of Manilaman Marcello Fabila, born in 1869 in Dancalan, Antique, Panay Island, Philippines.

The narrators, Emmanuel Ryan Ali-Torrisheba, sisters Micheline Lucille Fabila and Leoncia Geraldine Fabila, trace their lineage to three Manilamen—Albaniel, Torrisheba and Fabila.

(L-R) Ligouri, Joseph, and Katie

“[My great grandfather] Gregorio was a Manilla man... He travelled

to PNG in the 1890's. He married my great grandmother, Lele Saula from

Sideia Island, Milne Bay Province, PNG… My grandfather Pedro went on to

marry my grandmother, Katie Albaniel, the daughter of Manilla man, Nicolas

Albaniel.”

– Emannuel Ryan Ali-Torrisheba

Nicholas Albaniel

Micheline Lucille & Leoncia Geraldine Fabila...

Nicholas Albaniel

Micheline Lucille & Leoncia Geraldine Fabila...

LEONCIA GERALDINE FABILA

“[Our great grandfather] Marcello was a seaman and an adventurer who

traveled widely in Southeast Asia, Australia, and British New Guinea

(aka Papua). Before his calling as a catechist, he had worked as a pearl

diver on the luggers for 3 years.”

– Micheline Lucille Fabila

Emmanuek Ryan Ali-Torrisheba

Marcelo Fabila & Gregorio Torricheba...

Emmanuek Ryan Ali-Torrisheba

Marcelo Fabila & Gregorio Torricheba...

Marcello Fabila was born in 1869, in Dancalan, Antique, Panay Island, Philippines. Born from parents Hildephonso Fabila and Josephia Delgato, Marcelo was the youngest of ten children. He had worked as a pearl diver on the luggers for 3 years before being a catechist.

He joined the early missionaries of Yule Island’s Catholic Diocese in the Bereina District of the British New Guinea in 1898. Marcello worked as seaman on St. Andrew, the mission ship.

While working as a catechist, he met a Yule Island girl Raurau Ke’e, and married her in 1901. They had three children—Mika (Michael) Marcello, Kala (Salvatore) Marcello Fabila, and Juliana. Kala later married Ligouri, one of the daughters of Manilaman Nicholas Albaniel. Sisters Micheline and Leoncia, the narrators, traces their Filipino lineage to both their parents.

Another Manilaman, Gregorio Torricheba, came to Papua New Guinea in the 1890s, and was believed to be born during the mid to late 1860’s. He was a Catechist teacher, planter, and printer, who later married Lele Saula from Sideia Island, Milne Bay Province. They had five children—Emmanuella (b. 1903), Matthia (b.1904), Prudence/Podentio (b.1907), Pedro (b.1908), and Josephine (b.1910).

Pedro married Katie, another daughter of Nicholas Albaniel and together, they had five children. One of the children, Emmanuel, married Mary Monica Ali, the parents of Ryan Emmanuel Torrisheba, one of the narrators. Ryan’s Manilamen ancestors are from both sides of his parents, the Albaniel and Torrisheba family line.

After Gregorio’s death in 1910, his widow, Lele, married Francis Castro, also a Manillaman who was a catechist and boat builder from Panay Island, Antique Province.

“[My great grandfather] Gregorio was a Manilla man... He travelled

to PNG in the 1890's. He married my great grandmother, Lele Saula from

Sideia Island, Milne Bay Province, PNG… My grandfather Pedro went on to

marry my grandmother, Katie Albaniel, the daughter of Manilla man, Nicolas

Albaniel.”

– Emannuel Ryan Ali-Torrisheba

Nicholas Albaniel

Micheline Lucille & Leoncia Geraldine Fabila...

Nicholas Albaniel

Micheline Lucille & Leoncia Geraldine Fabila...

LEONCIA GERALDINE FABILA

“[Our great grandfather] Marcello was a seaman and an adventurer who

traveled widely in Southeast Asia, Australia, and British New Guinea

(aka Papua). Before his calling as a catechist, he had worked as a pearl

diver on the luggers for 3 years.”

– Micheline Lucille Fabila

Emmanuek Ryan Ali-Torrisheba

Magno Lloren...

Emmanuek Ryan Ali-Torrisheba

Magno Lloren...

Magno Lloren arrived in Torres Strait on 22 August 1899. He was the son of Mariano Lloren and Rosa Asis from Carigara, Leyte, Philippines. Magno worked as a diver and later a beche-de-mer (pearl fisherman).

He married Feliz(i)a Losbanes and together, they had five children, with only Isabella and Lorenzo having survived. He later married the children’s nanny, Luisa Carabello, after Felicia died at the age of 26. He later decided to return to the Philippines with Luisa and the three children.

Isabella married Cirilo Irlandez from Leyte, with whom she had six children, all born in Manila. Isabella and Luisa insisted on returning to Torres Strait, but this did not materialize. It was only in the early 1990s when Angelino, their third child, was granted Australian Citizenship by Descent, along with his siblings. He brought Isabella back to Australia in 1994.

The narrators, Angel Paterno and Lallaine Barrios, are Magno Lloren’s great grandchildren, along the lineage of Angelino. Lallaine brought her family to Australia in 1997, and in 1998 Angel moved to Sydney.

“I only saw Magno once when he lived in Sta Ana, Manila in the early

1970’s. He was dark, lanky, bald, and wore a white shirt. He never spoke

to me but I felt that his mind was far away and there was much sadness in

his eyes.”

- Angel Paterno

Magno Lloren

Lallaine Barrios...

Magno Lloren

Lallaine Barrios...

“In 1994, when dad came back to Manila after accompanying my ‘lola’ to

go back to Sydney, he told me that “we are going to Australia because

‘we’re Torres Strait Islanders.’” He told us that his grandfather was a

pearl diver in the Torres Strait.”

- Lallaine Barrios

Angel Paterno

Keeping the Filipino Connection...

Angel Paterno

Keeping the Filipino Connection...

Descendants trace their Filipino heritage through food, music, and dancing that came with the

incorporation of some Filipino words in the Broome lexicon. As one descendant recalled, “My father always used to say, “you’ve got to call the Chinese old people, lulu…and ti[y]o means uncle. We were taught that, see. Today, now our children, our grandchildren learn a different way, but they still use the word lulu.”

There have been attempts in the past by some of the Manilamen descendants to trace their family and relatives in the Philippines. Some descendants also returned to the Philippines and settled for good, as with the case of the Ybasco and Castillon Family.

On 18 October 2016, the Australian Embassy in Manila, in partnership with the Cultural Center of the

Philippines, showcased an exhibit based on the book, Re-imagining Australia: Voices of

Indigenous Australians of Filipino Descent, by Dr. Deborah Ruiz Wall with Dr. Christine Choo.

Descendants of Manilaman, Roma Puertollano, Patricia Davidson, Kevin Puertollano, along with others, travelled from Australia to Manila, and participated in the exhibition and traced their family’s roots.

The Puertollanos also embarked on a journey to Marinduque, their great grandfather

Thomas’ birthplace.

The search still continues to this day for some of the descendants who are still trying to piece together and trace their roots in the Philippines, the birth place of their Manilamen forebears.

“I remember just one dish that my dad and Uncle Owen used to make every

Shinju—dinuguan. It was like soul food… I remember what exactly what my

dad was wearing. He had one of those Filipino shirts (barong Tagalog)

and brown trousers.”

-mitch torres

Manilamen descendant

Connection

The decline of the natural pearling industry can be attributed to several factors—the introduction of cultured farming and the prevalence of plastic buttons in the 1950s. Moreover, the declining supply of natural pearls led to the imposition of bans and policies limiting its harvest to protect the species. Broome and the Dampier Peninsula in Northwestern Australia shares a common history with Southern Philippines—Sulu and Tawi-Tawi—when it comes to pearling industry.

These two areas, though separated by the seas, used to be a ground for Filipino divers, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike, who braved the depths of the water with their natural skills and limited equipment.